Let my words

become a sieve that sifts the soil, prepares it for the seed, the sower; let them be an inn with fire and food and company for tired travelers on their way; a stair, even a single step, by which you climb down, drawing near to whisper, Do not fear; a darkling thrush whose hallowed song cuts clear across the bleak expanse of hollowed time where water never turns to wine. Lord, take these jars and speak again, transfiguring my words to wine that only you can make, something divine, a holy offering— that wild and weary, lost and longing hearts would taste the Word, revive, and play their parts.

About the Poem

With five metaphors, this poem is meant to offer its gifts over time and through repeated prayers, so I won’t even attempt to discuss the whole thing. Instead, on the theme of our words inspiring others to play their parts, I want to offer three glimpses into this sonnet’s many debts to other people’s words.

The opening metaphor—“Let my words / become a sieve that sifts the soil, prepares / it for the seed, the sower”—is inspired by a quote from Irish poet Micheal O’Siadhail: “Just as I turn over my garden soil and shake it in a griddle to make it more kindly to the seed, so I hope that poetry might jostle the soil of the imagination, so that, when the sower [Christ] goes out to sow, the seed might fall on good ground.”1 There are so many ways our words can prepare people’s hearts and minds to be good soil for Jesus.

My poem’s fourth metaphor—let my words become “a darkling thrush…”—is inspired by Thomas Hardy’s famous poem “The Darkling Thrush,” in which Hardy contrasts his own “bleak” and “fervourless” experience of a dying world with the “full-hearted evensong” of a nearby thrush (a songbird). Even though the bird is “aged… frail, gaunt, and small,” it sings with such defiant joy that Hardy (an atheist) thinks it must know “Some blessed Hope” of which he is “unaware.”2 Likewise, I pray in my poem that God might make our words into “hallowed” instruments that awaken people from the “hollowed” and hopeless world they experience without God—a world where there are no miracles, “where water never turns to wine.”

This reference to Jesus’ miracle at the wedding in Cana leads into the poem’s culminating metaphor. I love how in this story Jesus doesn’t just make wine; he makes six huge jars full of “choice” wine, “the best” wine (John 2:10)—wine so good that the wine-lovers were surely waxing poetic trying to express its exquisite notes of “black fruit, leather, spices and earthiness.”3 Just as Jesus revealed his glory by turning everyday water into breathtaking wine, this poem-prayer asks God to transform our everyday words into “something divine, a holy offering” that reaches people where they are and helps them to taste, and respond to, the beauty and glory of God.

Even these few lines of this poem are indebted to the words of so many: Jesus, the four evangelists, Micheal O’Siadhail, Thomas Hardy, Malcolm Guite, and more—and this encourages me to think about how our words might inspire others as we speak, write, and live in prayerful partnership with Jesus the Sower, our Song, the Winemaker.

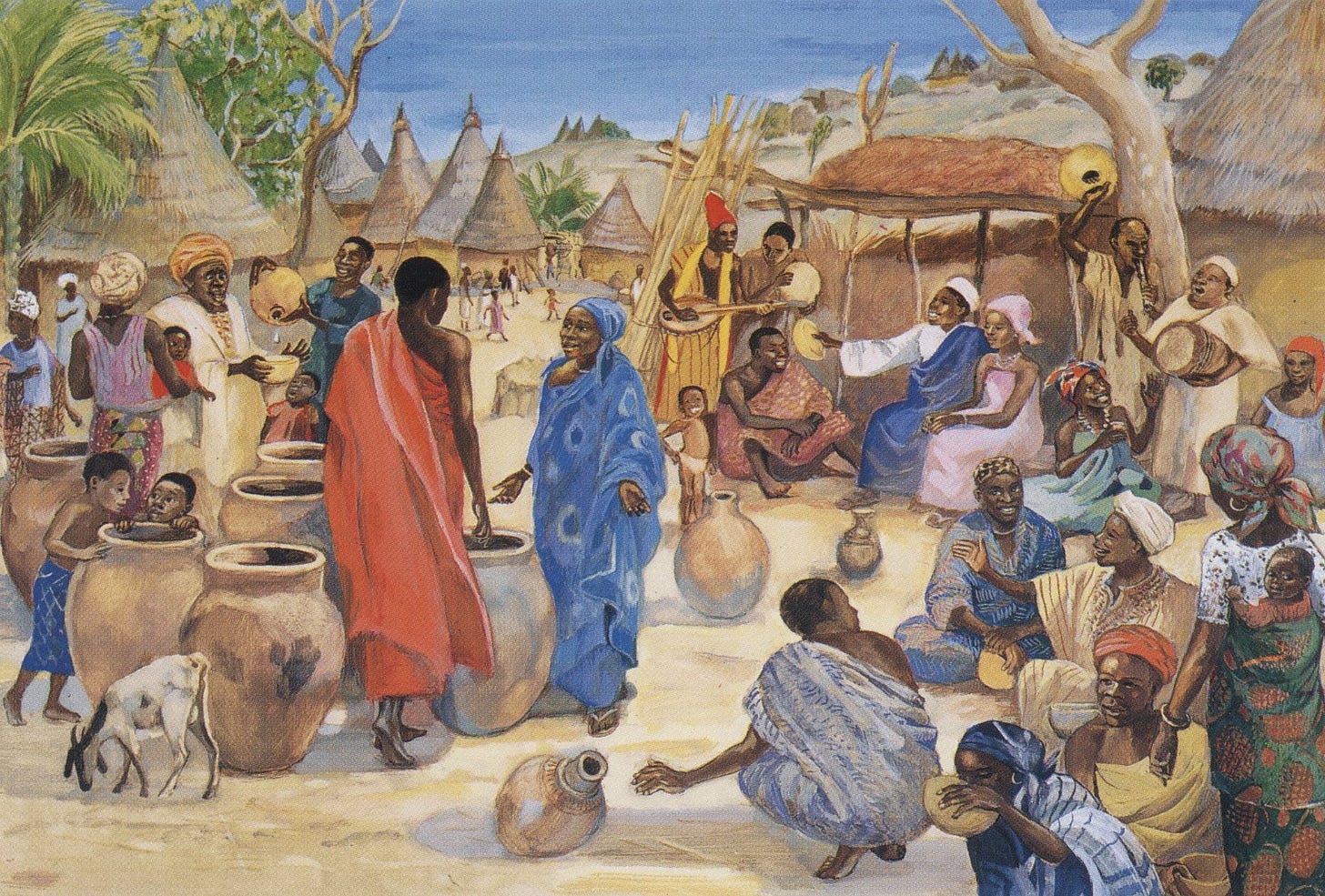

About the Painting

The painting above comes from the Vie de Jésus Mafa project in Cameroon. In the 1970s, French missionary François Vidil encouraged Mafa Christians to perform contextualized dramatizations of gospel stories, from which artist Bénédite de la Roncière then painted scenes. The collaboration produced over 60 paintings that helped the Mafa people and others relate the gospel to their own cultures—an inspiring creative collaboration!4

Thank you!

Thank you to Fathom Mag for originally publishing “Let my words.”

Finally, thank you for reading! I hope this poem and artwork are a gift to you. Please reply or comment with any thoughts. I’d love to hear from you!

Footnotes:

This quote comes from Malcolm Guite’s In Every Corner Sing: A Poet’s Corner Collection (Norwich: Canterbury Press, 2018), 64. O’Siadhail further explains that, in his understanding of the parable of the four soils, “Christ… is both the sower and the seed.”

I am again indebted to Malcolm Guite for his insightful analysis of Hardy’s “The Darkling Thrush” in chapter 7 of Faith, Hope and Poetry: Theology and the Poetic Imagination (New York: Routledge, 2016), which informed these lines of my poem.

Shout out to my friend Shamini (a.k.a. The Croffle Lady) who reads this newsletter. I read your wine reviews!

You can find the 60+ illustrations here in Vanderbilt University’s Art in the Christian Tradition database or in Bénédite de la Roncière’s book L’Evangile en Pays Mafa. The historical information comes from the Jesus Mafa blog.

Your poem says a lot! Then your addition on the metaphors you incorporated added yet more to that. I very much appreciated this.

So beautiful! Thank you for such an encouraging poem💕